Gallery

Many visitors have wanted to know who are the ikons represented on the walls of our church. This gallery explains who they are, explains a little of their history, and tries to convey that these were at one time, very real and living people who lived, breathed, had good days and bad days, had fathers and mothers and whose relationship with God was such that they offer a model for the rest of us. As far as possible, this gallery is arranged chronologically.

It would be easy for the non Orthodox to think that the vision Orthodox Christians had of the saints was only one of sycophantic blind acceptance of things we neither know nor understand. I want to stress that this is far from the case, but the reason we surround ourselves with the memory of these people is that they speak to us of God in ways that can deepen our own understanding of God. In the same way that Shakespeare speaks so profoundly of the human condition, if we are prepared to listen, the saints speak to us of the potential that the human relationship can have if we listen to God.

Ikons are opportunities God puts in our way to open a window into the eternal dimension. By taking the opportunity to pause before and ikon, we can remove ourselves from the present moment, from what we have been doing and what we will be doing, to focus on the presence of God, His angels and His saints. Ikons are a conduit through which we remind ourselves of how the ordinary became holy. How an ordinary day became transformed by God's miracle. How an ordinary person became so close to God they became extraordinary, and how by momentarily attaching ourselves to either miracles, the miraculous or the devoted to God, we can glimpse some of that special moment for ourselves.

Praying before an ikon, or a collection of ikons as one does with a domestic ikon corner, is to be as part of a crowd of people who love God and who will love God eternally. There is some real comfort in knowing you are not alone in your love of God, and by taking your place alongside others, through this window of ikons, you stand in the company of saints and angels before God to petition, adore, or simply 'be'.

Ikon above the Royal Doors

Along the top of the ikon screen in our church are a series of Ikons that depict scenes from the life of Christ and of his mother. This particular ikon, in the centre of the row, depicts not an event, however, but Jesus in the company of figures who hold special significance in the New Testament narrative. Jesus is the central figure and is shown seated on a throne holding the words I AM. This term is first seen in Exodus when we read "and God said to Moses, I AM that I AM, and He said, This will you say to the Children of Israel, I AM has sent me to you" וַיֹּ֤אמֶר אֱלֹהִים֙ אֶל־מֹשֶׁ֔ה אֶֽהְיֶ֖ה אֲשֶׁ֣ר אֶֽהְיֶ֑ה וַיֹּ֗אמֶר כֹּ֤ה תֹאמַר֙ לִבְנֵ֣י יִשְׂרָאֵ֔ל אֶֽהְיֶ֖ה שְׁלָחַ֥נִי אֲלֵיכֶֽם׃.

The key point of this ikon is that it emphasises the link to Jesus being the fulfilment of the Law and the Prophets, the promise to the people of Israel. The people depicted who surround Him, from left to right, Saint Peter, the Archangel Michael, Mary the Mother of God, John the Forerunner and Baptist, the Archangel Gabriel, and St.Paul.

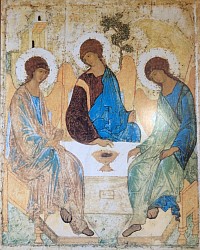

The Trinity

This ikon of the Trinity is a reproduction of one painted around 1410 by Andrei Rublev. It depicts the three angels who visited Abraham at the Oak of Mamre – but is often interpreted as an ikon of the Trinity. It is sometimes called the ikon of the Old Testament Trinity. The image is full of symbolism – designed to take the viewer into the Mystery of the Trinity. This ikon is reflected in the painting above the altar leading from the body of the church to the ikon of the Pantokrator. The imagery is that of the Eucharist, which is the central focus of the weekly church activity.

The Annunciation

The Annunciation is the story the church uses to describe how Mary was told she would be unaccountably pregnant. Joseph and Mary had gone through a ceremony of betrothal, promising each other they would consider themselves tied and unavailable to anyone else, at their local synagogue so their community would know that they intended to marry. In this arrangement they would live together but if this revealed that they were in fact incompatible the arrangement could be dissolved without embarrassment. Strictly speaking, couples were not supposed to share a bed or enjoy any intimacies.

This betrothal service meant that although neither was yet married to the other, Joseph couldn't consider another girl and no other man could cast an eye at Mary. Betrothal and marriage in those days should be thought of as civil ceremonies, with the (civil) law being Jewish law. Joseph and Mary may well have announced their betrothal "in the city gates" before the elders of the village. Betrothal was as binding as marriage and required a divorce decree to dissolve it; after the betrothal the couple were not permitted intercourse until the marriage. In traditional Orthodox belief, Mary in practice remained "ever virgin" even after the marriage took place, but in reality she was unlikely to have been a virgin sexually all her life. The accounts that James was also her son are credible,

The Nativity of Christ

In Orthodoxy, 'Theotokos' is the title given to Mary, and it means "Bearer" or "birth-giver" of God. The Orthodox church also refers to her as the 'Mother of God' (a title that stresses the divine nature of her son, Jesus). She is honoured in every service, and the Orthodox church marks also certain festivals (not only the nativity of her son) that recount events in her life. Some of these 'events' are recorded not in the gospels themselves but in the tradition that has been handed down, and these accounts are to be understood, not as reflecting an accurate historical account of what happened in reality, but rather as conveying to us her importance in God's plan of salvation.

This ikon, like some others, depicts a number of related events and not just one particular point in time. Thus, for example, we see Mary and Joseph travelling towards Bethlehem before Jesus' birth as well as events that occurred after his birth.

It cannot be ignored by any serious student of religion, that many religions in history elevated the feminine representation of the the progenitor of a god. In some ways, the characteristics ascribed to Mary of Christianity are also seen in the goddesses of other religions and cultures. For example, we see echoes of Minerva, Juno, Isis, Luna/Selene, Cihuacoatl, Devi, Guanyin, Hannahanna, Hathor, Heavenly Mother, Izanami, Leimarel Sidabi, Yumjao Leima, Varima-te-takere, Toci, Radha, Quiritis, Parvati, Nut and Maut. In Greek mythology, Leto gave birth to Apollo and Artemis, both gods. Rhea gave birth to Zeus.

Roman mythology holds up Rhea Silvia who as a virgin gave birth to Romulus and Remus (Parthogenesis). Similarly, in Egyptian culture Ra was born of Net, Horus was the son of Isis, more virgin births. Nana, gave birth to the Phrygia-Roman god Attis (oddly enough on December the 25!). Controversy surrounds Dionysos as to whether he was born of the virin Semele or persephone. Persephone is a good candidate as she also remained a virgin having given birth to Jason. Perictione remained virgo-intacta having delivered Plato.

Two thousand years before Christ, the virgin Egyptian queen Mut-em-ua gave birth to the Pharoah Amenkept III. Interestingly, Mut-em-ua had been told she was with child by the god Taht, and the god Kneph impregnated her by holding a cross, the symbol of life, to her mouth. Amenkept’s birth was celebrated by the gods and by three kings, who offered him gifts.

It goes on. Attis, a Phrygian-Greek vegetation god, was born of the virgin Nana. Some followers of Buddha Gautama decided he was born to the virgin Maya by divine decree. Genghis Khan was supposedly born to a virgin seeded by a great miraculous light.

Reflection and discernment therefore is required by the devoted Christian to attend their lives, attention and worship to God.

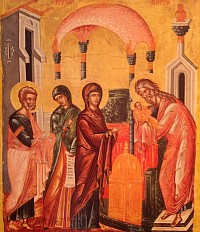

Presentation in the Temple

The feast of the Presentation of Jesus at the Templefalls on 2nd February, and celebrates an early episode in the life of Jesus. According to Jewish tradition and practice, firstborn male children had to be taken to the Temple and a sacrifice offered as laid out in Exodus. Joseph and Mary were devout Jews, as was Jesus, and the Law had to be fulfilled.

It was at this event that Simeon, who had been promised by God that he wouldn't die until he had seen the Jewish Messiah, took Jesus into his arms and said, "Now Lord let your servant depart in peace, for I have seen Your salvation. A light to enlighten the Gentiles, and the glory of Your people Israel".

The Baptism in the Jordan

The Baptism by John of Jesus in the Jordan is widely accepted by scholars as an historically accurate event. It either took place, it is believed, at Bethabera in Perea, or Enon near Salim. Rivers can be - and still are - used for Mikvehs - the water for ritual immersion has to be either rainwater or running water such as in a river. Men also went to the Mikveh, to be cleansed of ritual impurity such as that contracted by contact with a corpse. Many Orthodox men today will go to the Mikveh every Friday, before Shabbat, so they will be both physically and spiritually clean before the Sabbath. One must bathe, including washing one's hair, before entering the Mikveh. Any parts of the body "covered" by dirt are not considered to have come into contact with the "living" water of the Mikveh, thus nullifying the purification.

Baptism (a Greek word meaning 'washing') is a form of ritual washing that is a continuation of the ritual cleansing laid down in the Torah. The Torah required washing for a variety of reasons and occasions. Washing of utensils, the washing of the body, and the washing in a Mikvah after women had their period are all part of ancient Jewish life, and in many cases, modern Jewish life. One of these ritual washings were for those who wanted to convert to Judaism, marking the end of one life and the beginning of another with the washing away of the old life and renewal in the new.

Throughout his life, John sought to turn Jews from their old life which had become distant from God and to bring them through repentance to a renewed relationship with God. Jesus did the same. He continually sought to bring people back to God, from whom they had strayed. But to understand the significance of the baptism, which Orthodoxy sees as the start of Jesus ministry, one needs to look 200 years beforehand.

At that time there were three main strands which influenced Jewish thinking, and, of course, the thinking and experiences behind the ministries of both John and Jesus. The Pharisees (the ancestors of today's Judaism), the Sadducees (the Temple priesthood) and the Essenes (meaning 'pious ones'). The Essenes were probably an offshoot of the Pharisaical school, but took a rather rigid adherence to the Law to bring them closer to God. The Sadducees, who disappeared around AD 70 after the destruction of the Temple, didn't believe in an afterlife, while Essenes and Pharisees did. While the Essenes and the Pharisees were focused on the letter of the Law, Jesus wanted to bring people awake to the spirit of the Law.

One branch of the Essenes organised themselves into fraternities, praying together, worshipping together in their homes, and eating communal meals together. Some scholars have suggested that Jesus, when he gathered the apostles and disciples into His own fraternity, was influenced by this example, and that as a result the early church had very similar beliefs in certain respects. Other scholars have seen John the Baptist in a similar light.

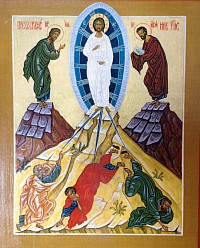

The Transfiguration

The Transfiguration of Christ is one of the Great Feasts of the Orthodox Church and is celebrated on August 6th each year.

It commemorates the event, described in the gospels, when Jesus had gone with his disciples Peter, James and John to Mount Tabor. Christ's appearance was changed while they watched, into a glorious radiant figure. There appeared Elijah and Moses speaking with Jesus (though we are not told how Moses and Elijah were recognised as no images of either were known then or now). The account describes the Transfiguration close to the Passover, but given that the disciples offered to build Tabernacles for the three it could be believed that Christ's transfiguration took place at the time of the Jewish Festival of Tabernacles (harvest time around autumn), and that the celebration of the event in the Christian Church became the New Testament fulfillment of the Old Testament feast. The Orthodox Church connects these two feasts to help Christians understand the mission of Christ and that his suffering was voluntary.

Raising of Lazarus

Lazarus and his sisters are family friends and while Jesus is in the area of His baptism, he gets a message that Lazarus is ill. Jesus delays going there convinced that by so doing He will be able to do something even more remarkable than by heading death off at the Pass. Four days after Lazarus dies Jesus turns up at Bethany near Jerusalem on the Jericho road. According to custom and Law, Lazarus is already entombed. Jesus states that the stone should be removed from the tomb entrance. Quite reasonably Martha objects. Lazarus, remember, had been sick for a long time, in an age without antibiotics. The death, we are told, is related to disease and not a fracture, thus we can reasonably ascertain that decay was long advanced before Lazarus died, never mind the extent of decay in the heat of a Middle Eastern sun four days post mortality. The anticipated whiff of putrefaction must have been terrifying. Following Jesus shouting for Lazarus to come out, Lazarus emerges, oil embalmed, cloth bound, shuffling and staggering into the sunlight.

Christ enters Jerusalem

The gospel account states that whilst Jesus regularly went to Jerusalem to teach and attend the Temple, all four gospels record Jesus arriving at Jerusalem on a donkey in order to celebrate the Passover, when the Israelites were spared the Angel of Death by marking on their door lintels the blood of a lamb. This took place in the month of Nisan (around March - April), a month during which many momentous events in Jewish history have taken place Recent studies have suggested March 30th AD 33 as the probable date.

During the Passover, animals were donated to the Temple free for use by any holy man in service to God. They were gifts made as part of a mitzvah (something done freely for the benefit of others that would bring the giver closer to God). Thus, whenever any man was seen riding just such one of these donkeys during the Passover they would be recognised by the crowd as an important and holy person.

Five days before the Passover began (a Monday) Jesus sent disciples to fetch one of these animals and as He rode into Jerusalem John's (only) account claim He was welcomed by crowds waving Palm branches and spreading clothing in His path. Palm branches represented both joy and triumph to Israelis at the time, and the practice of laying clothes in the path was one afforded to kings. Jesus was recognised as the one who had brought back Lazarus from death and as such enormous expectations were held of Him by the Israelis. This excitement was viewed rather dimly by the Pharisees and Sadducees as their own influence and power over devout Jews was diminishing before their eyes, an opinion confirmed by what happened when Jesus arrived at the Temple.

There is a difficulty with this account because the waving of palm fronds is associated not with Passover but with Succoth, the Feast of Booths. Waving of palm leaves is associated not just with warding of evil and the bringing of good luck but also to symbolise honour and victory. The date palm (Lulav) is one of four species of palm use in the daily prayers during the feast of Succoth. It is bound together with myrtle (hadass)and willow (aravah). In this context, as explained by the Midrash, palm symbolises the victory of Jews when they came before God on Rosh Hashanah. It is quite credible that the authors of the New Testament conflated Succoth with events at Pesach because there is no obvious reason why Jesus was welcomed into Jerusalem just before Pesach as a victor, but to celebrate Succoth people would wave palm leaves as described above in the same way that football fans would wave scarves on match days. It has to be borne in mind that gospels were written many years AFTER the resurrection and are not a contemporaneous account as newspaper articles are. The feast of Succoth (Booths or Tabernacles) takes place in Autumn months apart from Spring and Pesach. As the late Queen said, "recollections may vary".

To fulfil the requirements of Passover, strict rules are laid out for the cleansing not only of houses but also of the Temple. Over time, trading in the Temple had evolved to include not only legitimate businesses selling livestock for sacrifice (lambs doves etc) but also traders selling stolen shoddy and second hand goods. The equivalent would be a car boot sale taking place in St Peter's Basilica! It was rage at this that sent Jesus trashing the stalls holders in the Temple.

After this Jesus left Jerusalem and made His way to Bethany, a suburb of Jerusalem where archeology has found that it was populated heavily by Essenes, a community to which Jesus has been frequently linked, where He remained to hold the Last Supper which was, according to some scholars, possibly a Seder. Some say that it was common at the time for Seders to take place over a period of days rather than on one particular day, and the Last Supper is held to have taken place on the Wednesday. Others confidently say that this would have taken place on just one day, 15th Nisan, in accordance with the day set out by the Torah. The Talmud relates that one of the recurring miracles was that everyone had room to prostrate themselves on Yom Kippur when the High Priest pronounced the Name of God, even though there was barely enough room for everyone to stand. The Temple had very strict rules as to how people entered and left the Temple on Pesach, and how many were let in at a time, so that everyone could sacrifice their lambs in the Temple courtyard on the afternoon of the 14th, as required by law, without any crushes occurring. It is estimated that perhaps as many as a million people were in Jerusalem during Pesach, Shavuos and Succos.

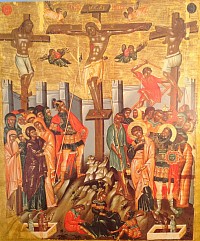

The Crucifixion

In his early thirties, Jesus of Nazareth was crucified under Roman Law by edict of Pontius Pilate (reluctantly it is believed) who had been placed in an impossible political position by the Pharisees and Sadducees. According to Roman Law, the crimes for which a prisoner was crucified were nailed on a board above their head. Because Jerusalem was a polyglot society, criminals had their crimes written in the three main languages of that society. Thus, Pilate had ordered that in Greek, Latin and Hebrew was written 'Jesus of Nazareth. King of the Jews'. Jerusalem was politically legally culturally and ethnographically cosmopolitan. It was this richness of population that deemed that we know Christ by His Greek Name (Jesus) and not by His Hebrew Name (Joshua Bar Joseph - meaning Joshua son of Jospeh).

** With thanks to a critique of "the Innocence of Pontius Pilate: How the Roman Trial of Jesus Shaped History", David Keys, (Hurst) the following throws light in an obscure period;

New historical research is shedding fresh light on the birth of Christianity as a major religion. Although Christianity had existed since the mid-first century AD, it didn’t become the Roman empire’s main religion until more than 250 years later. Now, new research is revealing the dramatic pro-Christian and anti-Christian propaganda wars which preceded Christianity’s emergence as the empire’s dominant faith.

An investigation by an American historian of early Christianity, David Lloyd Dusenbury of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, is for the first time establishing the scale and nature of the propaganda battles that raged in the final decades of pagan control of the empire.

The new research, shows that a major issue used by both sides in the late third and the very early fourth century was the role of Pontius Pilate, the Roman prefect of Judaea who had ordered Jesus’s crucifixion some 270 years earlier. The battle seems to have centred around Pilate’s actions. Both sides wanted Pilate, a traditional high-ranking Roman, to appear innocent of any wrongdoing – but in different ways.

The new research suggests that the pagans tried to vindicate Pilate by claiming that Jesus was a violent and dangerous rebel – and that therefore Pilate was quite right to have had him executed.

By contrast, many Christian propagandists sought to exonerate Pilate by claiming that the Jews had taken matters into their own hands – and that therefore it was the Jews, not Pilate, who were to blame for Jesus’s death.

Although the pagan/Christian ideological war was ultimately decided on the battlefield, both sides appear to have seen their respective propaganda campaigns as essential in increasing their chances of political and military victory.

At the time, it’s estimated that only around 10 per cent of the population of the empire was Christian. Of the remaining 90 per cent, most were pagan.

And yet, with the help of pro-Christian propaganda, Christianity succeeded in winning over sufficient high status and powerful individuals to enable it to triumph politically and militarily.

On the pagan side there were two key propagandists: one was the rabidly anti-Christian Roman ruler of Syria, Palestine and Cyprus, a Roman soldier called Maximinus Daza, who became co-emperor between AD310 and 313.

He was the promoter of the main pro-pagan book, entitled Memoirs of Pilate, which sought to justify Pontius Pilate’s decision to crucify Jesus. He claimed that the book was based on Pilate’s own (now long-lost) account of Jesus’s trial, an account which had apparently been sitting in an imperial library for the preceding 270 years.

Daza was an eastern European of peasant stock, who was accused by Christian propagandists of being a sex-mad, alcohol-obsessed, debauched serial adulterer. Apart from a very brief pagan comeback half a century later, he was the last pagan emperor of the empire, and was also (as Roman ruler of Egypt) the last and roughly 210th person to have the title of pharaoh.

The other key pro-pagan propagandist was the Roman governor of Bithynia (northern Turkey), a Roman aristocrat and philosopher by the name of Sossianus Hierocles who wrote an anti-Christian propaganda book called Lover of Truth, which seems to have accused Jesus of being the leader of a 900-strong gang of robbers!

Although it’s extremely unlikely that Jesus was in any way involved with such outlaws, first and early-to-mid-second century Judea would have been perceived by many educated Romans as a hotbed of violent, and often messianically inspired, rebels and politically motivated “robbers”. Indeed, in the century and a half following Jesus’s birth, there were at least a dozen partly religiously motivated armed Jewish rebellions against Rome in at least five different parts of the empire (including at least seven in Judea itself). The empire’s Jewish population, especially the Jews of Jesus’s era, was without doubt one of its most rebellious, a reputation which anti-Christian propagandists appear to have exploited to the full.

On the Christian side there were also two key propagandists, the most aggressive of whom was a stridently anti-pagan imperial adviser named Firmianus Lactantius, who produced anti-pagan and anti-Jewish propaganda material. In one book, The Deaths of the Persecutors, he describes in lurid detail how God inflicts particularly gruesome deaths on political leaders involved in anti-Christian campaigns. And, in another book, The Divine Institutes, he spread totally fake allegations that the Jews (not the Romans) had actually carried out Jesus’s crucifixion – and that Pilate had never sentenced Jesus to death. Lactantius was a key adviser of the first Christian emperor, Constantine, but he was also, to a large extent, a progenitor of Christian antisemitism.

Another key pro-Christian campaigner was a Christian theologian and historian called Eusebius who wrote a book known as Martyrs of Palestine in order to discredit the pagan Roman rulers who controlled that region. The book was an expose of pagan brutality, and a work of praise for Christian heroes.

“Prior to carrying out this new research, we had never realised how large the figure of Pilate loomed in the huge propaganda war that preceded Christianity’s triumph over paganism,” said Dr Dusenbury, who has just published his revelatory new research in The Innocence of Pontius Pilate.

Although the least Christian part of the empire was Europe, it was from there that the most powerful pro-Christian political leader, a ruthless senior Roman military officer called Constantine, emerged. Conversely, it was the empire’s Asian provinces which had the largest Christian populations – but also, perhaps as a consequence, some of the most virulent anti-Christian political leaders. It is conceivable that in the east, Christians were seen by some of their pagan fellow citizens as a threat, while in some parts of Europe, Christianity was not perceived so strongly in that way.

The key accusation against Jesus concerned his alleged claim to be King of the Jews (albeit not in the conventional political sense). Pontius Pilate had referred Jesus’s case to the ruler of Galilee, Herod Antipas, but Herod refused to convict and referred the case back to the Roman prefect. Pilate then finally tried Jesus and found him guilty.

Some historians have been puzzled over why Jesus’s alleged claim of royal status (even if only in a spiritual sense) would have been a Roman capital offence. The answer may lie, by a bizarre coincidence, around the year of Jesus’s birth, in an event 1,400 miles to the northwest.

For, around the year 1BC, the Emperor Augustus had finally settled a Middle Eastern political dispute between different claimants to the Judean throne (ie, to the title “King of the Jews”) by indefinitely suspending the use of that title. Indeed the title itself was, in legal terms, a Roman “possession”, having been specifically created some years earlier not in Jerusalem, but by the Senate in Rome.

Jesus’s alleged claim to be “King of the Jews” may well therefore have been perceived as violating that imperial legal decision to suspend that Roman-originating title. Although Jesus himself never confirmed or denied that he claimed that title, the Romans and others perceived that he did.

The propaganda conflict which preceded the triumph of Christianity occurred between roughly AD290 and 313, and as that battle intensified, the struggle between pro-pagan and pro-Christian forces became a more physically violent one. First, between 303 and 313, a succession of pagan Roman emperors launched a brutal suppression of Christianity (mainly in the east of the empire). But, in the final few years of that period, armies, led by pro and anti Christian emperors, began to clash.

The two key battles were in AD312 when Constantine, who had been declared emperor by the Roman legions in Britain six years earlier, defeated his pro-pagan rival near Rome – and in the following year, when the emperor Maximinus Daza was defeated by Christian-aligned forces near what is now Istanbul. ***

His crucifixion took place on a Friday, and concern was raised that He wouldn't be dead by dusk on Friday, as that was the beginning of the Shabbes.

Jewish Law stipulated that there should be no one still alive on a cross by the time the Shabbes began. Jewish law forbids crucifixion, indeed, Jews revolted more than once when the Romans, within Judea, crucified people. Jewish law stipulates that, if a man is hung, his body is brought down by nightfall. Jewish law also stipulates that the dead are buried within 24 hours of death, and that no one is left unburied over Shabbes.

Crucifixion was a slow painful and lingering death, occasionally made easier by those compassionate enough in the crowd (often family members or friends) passing up a hypnotic drug contained in vinegar suspended in a sponge. Despite being offered a sponge, Jesus refused this aid. Death in this way placed enormous strain on the cardiac and pulmonary systems. As the arms are stretched by the weight of the body, the rib cage is impaired from movement leading to slow suffocation. To spread the torture and punishment out a little longer, prisoners had their ankles bound or nailed to a ledge upon which they could push themselves to help their breathing. This in turn added to their pain as they were pushing against the nails in their ankles. Eventually weakened by all this they died, sometimes days later. To avoid being left till after the Sabbath, Roman soldiers were instructed to break the bones to hasten death by preventing them from breathing longer. Unusually, Jesus had died by this time and the soldiers instead thrust a spear into his abdomen, from which fluid drained. This fluid is quite possibly a product of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Oedema caused by the crucifixion, where the heart being unable to pump effectively, backed up blood and fluid decreasing the volume of blood the heart could pump round, leading to fluid building up in the lungs.

The crucified were stripped naked to compound their humiliation, though Christian art applies modesty to the depiction. Everything possible was done to make the torture of crucifixion as cruel as possible. The condemned were made to carry the instrument of their death through the streets, witnessed by the crowds, outside the city walls to the place of execution. On the day in question, we know of two others who were crucified with Jesus. As the condemned were being prepared for death, it was a perk of the job for the soldiers on duty to divide the possessions the condemned among them.

In particular Jesus was stripped of his expensive seamless robe which was woven top to bottom and was identical to that worn by Priests serving in the Temple. It is unclear if it was the techelet,which was 12 ply sky blue dyed wool, or, possibly more likely, made of six ply woven white flax, the sort of robe the High Priest would have worn on the Day of Atonement. The High Priest would have two sets, one for use in the morning and one in the evening, and he only wore these once. The robe was a closed garment and slipped on over the head. The opening at the neck was round, with a hem that was doubled over and closed by weaving-not by a needle. The garment hung down in front and in back, and its length extended all the way down to the priest's feet. There is a difference of opinion as to whether there were sleeves, but if so these would also have been seamless and attached separately.

(Incidentally, this robe is akin to the same as the robe worn by patriarch Joseph but, due to an oft repeated mistranslation, was called a "coat of many colours", and was in fact white).

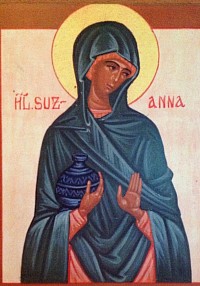

St Susanna the Myrrh Bearer

This Susanna refers to the Susanna mentioned in Luke's gospel chapter 8. This is the only time she is mentioned by name in the gospels, but it is assumed by the church that when 'The women' (Luke 23) came to anoint the body of Jesus, Susanna was one of them.

The crucifixion took place on a Friday, just before the beginning of the Jewish Shabbes (sabbath), and in accord with the strict traditions of the time there was no time to fulfill all the burial customs of Jewish Law. As such, Jesus was laid in a borrowed tomb to await the time after the Shabbes had ended for the burial customs to be completed. Thus it was that, at dawn on Sunday, a group of women arrived at the tomb laden with the necessary articles to complete the burial rites according to Jewish law and custom. Among the items necessary for this purpose was Myrrh.

The origins of this can be found as far back as Exodus (30:22-25, 32-33). Myrrh is a reddish resin that oozes and is dried from species of the genus Commiphora, which are native to northeast Africa and the adjacent areas of the Arabian Peninsula. Commiphora myrrha, a tree commonly used in the production of myrrh, can be found in the shallow, rocky soils of Ethiopia, Kenya, Oman, Saudi Arabia and Somalia. Thus, we know it was expensive as it had to arrive in Israel from across such lengthy trade routes. To make into oil this dried sap has to be distilled.

Arriving at the tomb, the 'myrhh-bearing women' (as they are usually called in Orthodox texts) found that the tomb was empty. It was thus not Jesus's male followers, but the women who had cared for him, who were the first witnesses of the resurrection, and in Orthodoxy this group of women have a far higher profile than in any strand of Western Christianity.

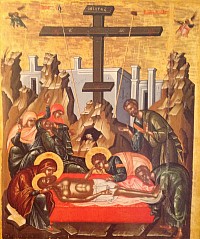

The Descent from the Cross

To avoid transgressing the rules of the Shabbes (they would have hurried home for the Sabbath meal because one does not mourn on the Sabbath) Jesus was taken down from the cross, wrapped in a linen shroud and taken to a tomb owned by a man named Joseph. In Orthodoxy we remember this at every liturgy, and at Pascha we mark the event by the sung words of "Noble Joseph,having taken down the body of Jesus from the cross, wrapped it in linen and spices and laid it in the tomb". At Pascha on Good Friday the church becomes the tomb and the altar the site of crucifixion, when during that service the shroud bearing the image of Christ is brought from the altar to the place laid out in honour and decorated with flowers as though Joseph himself, with the followers of Jesus, were bringing it themselves.

As Christianity spread across the world, pagan rites and practices were adopted by clergy and missionaries to enfold cultures into Christianity. This in many way is why Mary hold the position she does in Christian tradition. The cult of Mary is simply a reflection of how Christianity enfolded old religions worshipping fertility goddesses into the Christian perspective so as to make it easy for pagans to be converted. Acts 17:16 - 34 describes how Paul preached to Athenians about how their worship of the "Unknown God" was actually the God who we know to be the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob.

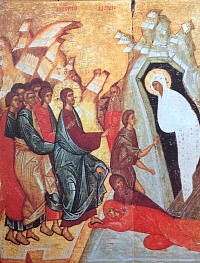

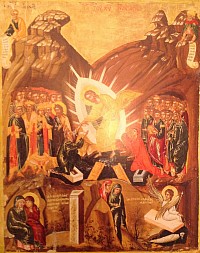

Descent into Hell (the Resurrection)

Both the Apostles' and the Athansaian Creed state that following His death, Jesus descended into the place of the dead, Hades. The Orthodox services at Pascha (Easter) strongly stress the way in which "trampling down death by death" Christ bestowed life on those in the tombs, and the ikon shows some of the most important of those in the tombs - including Adam and Eve - being freed from death. This indicates that the whole of humanity - those who lived before Christ as well as those who lived after Him - are the beneficiaries of his life, death and resurrection.