Fasts and Feasts

For Orthodox Christians, fasting and feasting are important parts of our discipline. We believe it is right and proper to use fasting and discipline to bring us to God, and equally we recognise that there are times in the calendar where we should celebrate. Lent and Advent, for example, are times of penitence and preparation for the feast to follow. Pascha (Easter) is a time to rejoice and celebrate. A component within Orthodox life preparatory to the great feasts is confession; there are a variety of essays on this that might assist understanding confession, but St John of Kronstadt wrote a check list, a revised version of which may be found here.

As with much of Christianity, because the roots of our faith emerged from Judaism, we can trace the practice of fasting back to the earliest of days where it was practiced either as a preparation for a spiritual meal, a method for inducing a state that would be open to transcendental experiences, or as a means to provide new vitality during periods of being barren. David, Saul, the prophets, the saints and Christians today have elected to fast for various reasons.

For the Christian, all foods are clean. When no fast is prescribed, there are no forbidden foods.

For fasting days, the following information may be helpful.

The Orthodox church does not make the distinction between "fasting" and "abstinence" that is sometimes made in the West. The strict rules simply indicate that on any fasting day the following foods should be avoided: Meat, including poultry, and any meat products. Fish (meaning fish with backbones, since shellfish are permitted). Eggs and dairy products (milk, butter, cheese, etc.). Olive oil. Wine and other alcoholic drink. (In the Slavic tradition, however, beer is often permitted on fast days because - until recently - beer was considered food.)

When the feasts of some major saints fall on what would otherwise be fasting days, the fast is still kept but wine and olive oil are permitted. These days are indicated in the calendar. Similarly, Saturdays and Sundays in the main fasting seasons (see below) are also "wine and oil" days.

Although these rules may appear quite strict to those who have not seen them before, they were developed with all of the faithful in mind, and not only monks. (Monks do not eat meat, so rules regarding the eating of meat cannot have been written with them in mind). However, we should bear in mind that the circumstances and dietary habits in which they were developed were different to those in which many Orthodox now live, and it is the spirit rather than the letter of the rules that is important. Nevertheless, although few laypeople are now able to keep these rules completely, it is desirable for those wishing to follow the Orthodox way to find as close a compromise to the strict rules of fasting as fits in in with their own lives. (Those eating in works canteens or living in households containing non-Orthodox members will find this issue more difficult than others and in these cases, in particular, compromise is quite proper but should ideally be discussed with a priest or spiritual guide).

It should be noted that it is neither permitted nor required that you endanger your health by fasting. This means, for example, that abstinence from food that leads to dangerously low levels of blood sugar - which in turn endangers yourself or others - is not good practice. However, avoiding prohibited foods usually poses no health risk as long as adequate amounts of other foods are taken. When fasting, we should eat simply and modestly. Monastics eat only one full meal a day on fast days, two meals on "wine and oil" days. However, laypeople are not usually encouraged to limit meals in this way.

Exceptions

The Church has always exempted small children, the sick, the very old, and pregnant and nursing mothers from strict fasting. However, while people in these groups should not seriously restrict the amount that they eat, no harm will come from doing without some foods on two days out of the week — simply eat enough of the permitted foods. Exceptions to the fast based on medical necessity (as with diabetes) are always allowed. It also must be acknowledged that where households consist of both Orthodox and non-religious members, the unity of the family transcends the rules of fasting, where to fast would lead to conflict.

Fasting Seasons

The fasting seasons - of which the main one is the Great Lent - are indicated in the calendar. Note that Saturdays and Sundays in these seasons are usually "wine and oil" days.

Weekly Fast

In addition to the main fasting seasons, Orthodox Christians are encouraged to keep a fast every Wednesday and Friday unless a fast-free period is indicated in the calendar.

Communion Fast

So that the Eucharist may be the first thing to pass our lips on the day of communion, we abstain from all food and drink from the time that we retire (or midnight, whichever comes first) the night before. When communion is in the evening, as with Presanctified Liturgies during Lent, this fast should, if possible, be extended throughout the day until after communion. For those who cannot keep this discipline, a total fast beginning at noon is sometimes prescribed.

The Lenten Fast

Great Lent is the longest and strictest fasting season of the year.

During the week before Lent ("Cheesefare Week"), meat and other animal products are prohibited, but eggs and dairy products are permitted, even on Wednesday and Friday.

First Week of Lent: In the monastic tradition, only two full meals are eaten during the first five days, on Wednesday and Friday after the Presanctified Liturgy. Nothing is eaten from Monday morning until Wednesday evening, the longest time without food in the Church year. (Few laymen keep these rules completely). For the Wednesday and Friday meals, as for all weekdays in Lent, meat and animal products, fish, dairy products, wine and oil are avoided. On Saturday of the first week, the usual rule for Lenten Saturdays begins (see below). Laypeople - as on other fasting days - are encouraged to follow the spirit of these rules even if keeping them to the letter is inappropriate to their circumstances.

Weekdays in the Second through Sixth Weeks: The strict fasting rule is kept every day: avoidance of meat, meat products, fish, eggs, dairy, wine and oil.

Saturdays and Sundays in the Second through Sixth Weeks: Wine and oil are permitted; otherwise the strict fasting rule is kept.

Holy Week: The Thursday evening meal is ideally the last meal taken until Pascha. At this meal, wine and oil are permitted. The Fast of Great and Holy Friday is the strictest fast day of the year: even those who have not kept a strict Lenten fast are strongly urged not to eat on this day. After St. Basil's Liturgy on Holy Saturday, a little wine and fruit may be taken for sustenance. The fast is sometimes broken on Saturday night after Resurrection Matins, or, at the latest, after the Divine Liturgy on Pascha.

Wine and oil are permitted on several feast days if they fall on a weekday during Lent. Consult your parish calendar. On Annunciation and Palm Sunday, fish is also permitted.

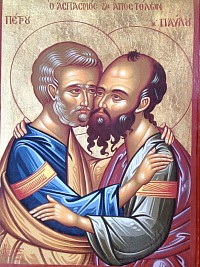

Apostles' Fast

The Apostles' Fast begins the second Monday after Pentecost and continues till June 29th, when we celebrate Saints Peter and Paul. The rule for this variable-length fast is more lenient than for Great Lent.

Monday, Wednesday, Friday: Strict fast.

Tuesday, Thursday: Oil and wine permitted.

Saturday, Sunday: Fish, oil and wine permitted.

(This is the rule in practice kept by many monasteries during non-fasting seasons).

Nativity Fast.

During the early part of the fast, the rule is identical to that of the Apostles' Fast. During the latter part of the fast, fish is no longer eaten on Saturdays or Sundays. In different traditions, this heightening of the fast may be for either the last week or the last two weeks

Dormition Fast

August 1st to the 14th is when Orthodox tradition marks what is called the Dormition fast, since it precedes the commemoration, on 15th August, of the Dormition (falling asleep in death) of Mary.

Obviously Mary didn't bypass death in the literal sense, though there are some misguided people who believe she did. Some believe she was translated immediately into heaven, which, in the Roman Catholic tradition, is part of the dogma referred to as her "Assumption". Although this belief is also held by many Orthodox, it is not part of the dogma of the Orthodox Church, and not something to which every thinking Orthodox Christian subscribes.

During this fast, meat, dairy products, fish, oil and wine are avoided, though wine and oil are allowed at weekends. The fast is followed by the Dormition Feast.

Koliva

Koliva is a dish that is blessed at the end of the Holy Liturgy, and arrives in church from a member of the congregation who wishes to celebrate the memory of dead family and friends. Traditionally it is made with boiled wheat, but finding wheat to boil isn't easy in this country, so where necessary wheat cous cous is used, though both rice and barley are also used. When boiled it is sweetened with honey or sugar, and pomegranate seeds, almonds, raisins, sesame seeds and ground walnuts may be added. It is formed in a mound to resemble the grave, and recalls the sweet memory of the departed.

It is a touching moment, and though we are bereft of those who have died, we hold their memory in honour and 'don't 'try and sweep them under the carpet'. For Orthodox the departed are very close to us in Christ. We pray for them and trust that they pray for us.

The Orthodox Year

The Orthodox year begins liturgically on September 1st. The original reason for this was that in the region in which Christianity began and from which it spread, people's lives were dependent upon the agricultural cycle. Thus, the end of harvest was the end of the agricultural year and the end of the liturgical year. September 1st marked the point when people began preparing for the new agricultural year and thus it was appropriate that people began the new liturgical year. Liturgically we begin our year with readings that mark the beginning of the ministry of Jesus.

The first feast after Sept 1st is the Nativity of Theotokos on Sept 8th. The feast of the elevation of the cross follows on 14th September, followed on 21st November by the presentation of Theotokos in the Temple. The Nativity fast begins 40 days before Christmas, with the Nativity being celebrated on 25th December. (See notes on the Old and New Calendars below.) Theophany - the feast that marks the baptism of Jesus in the Jordan - is on 6th January, after which and priests visit the houses of those in their care to conduct house blessings. The feast of the Presentation in the Temple is on 2nd February, after which comes the moveable feast of Pascha (Easter) preceded by the Great Lenten Fast. The feast of the Ascension follows accordingly. The 2nd Monday after Pentecost we mark the Apostles fast and somewhere in all this on 25th March will be the feast of the Annunciation. The feast of the Holy Transfiguration takes place on 6th August in the middle of the Dormition fast (1st to 14th August.)

There are daily feasts of saints on all other days in the year; a full list may be found here.

THE OLD AND NEW CALENDARS

Our parish follows the so-called "New Calendar", and since the problem of the calendar is often one that divides Orthodox Christians, this term perhaps requires some explanation.

One problem that arose in the early church was that of exactly how the church's calendar should be calculated. It was agreed, for example, that Pascha should be celebrated (following Jewish understandings of when the Passover should be celebrated) on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the Spring equinox. But how would people know when this was actually the case? (In seventh century Britain, those following the calculation used in Ireland found themselves at odds with those following the calculation that was used in most of Europe and Asia, and only gradually - after the Synod of Whitby in A.D.664 - did the majority view prevail.)

What eventually prevailed throughout the Christian world was a calendar based on the very best astronomical calculations available in the late antique period. The trouble was, that these calculations were not absolutely accurate. The date of the actual Spring Equinox (and every other day of the year) in this calculation fell behind the reality by about three days in every four hundred years, and the calculation of the full moon's date was also less than perfect.

In the West, the disparity between the official calendar and the reality of God's world made it clear that a "new" calendar would be necessary, which would incorporate new and better calculations of the year's length and, by skipping a number of days, would get things back on track. This calendar appeared in the sixteenth century and was adopted in the Roman Catholic world. It was only gradually accepted in the Protestant world, however, so that in England, for example, it was adopted only in the eighteenth century (with accompanying riots among those who felt that eleven days - which needed by this time to be skipped - had been stolen from their lives.)

In the Orthodox world, no change was made until the early twentieth century, and then only in a piecemeal way, with some Orthodox churches still being unwilling to make the change. The result is that some parts of the Orthodox world still keep the old calendar while others keep the new, and these two calendars are now thirteen days apart. Thus the feast of the nativity on 25th December is kept by some (like those in our parish) on the true 25th December and by others (e.g. in Russia) on what is ecclesiastically, for them, 25th December, but is in reality (and in their secular calendars) 7th January.

A further complication is that those who adopted the new calendar decided, for good pastoral reasons, that it was important that all Orthodox Christians should celebrate Pascha on the same day. Thus it was agreed by them that the calculation of the date of Pascha - the greatest feast of the Christian year - would continue to use the old calendar and calculation until such time as the new calendar had been adopted throughout the Orthodox world and the matter looked at properly. The result is that Orthodox Pascha - which properly (that is, astronomically) speaking should occur on the same Sunday as Western Easter - can in practice be on the same day but can also be up to six weeks later!

The Blessing of Houses

Every year just after the Feast of Theophany, it is the normal practice for priests to visit the homes of Orthodox Christians to bless each household. Non Orthodox might think this odd, but it is to pray that where people live may continue to be a place of refuge, comfort, security, joy, reward, and peace. It is NOT for the purposes of the priest to inspect the house for being neat tidy dusted or that the household ikons are straight. A priest ought not care one bit how someone chooses to live provided they are safe happy and well. How does it happen? It happens thus. The priest will arrive as agreed previously on a day and time that suits all, and with those in the house will stand in front of the main ikons and pray a small litany. Then, singing the Troparion for the Feast of Theophany, he will move from room to room sprinkling with blessed water. That's it. All done in as much time as it takes to walk from room to room. He will usually have lots of people to see in as short a time as possible so it doesn't take up hours.